Discontinuous Semver: Versioning in the Land of Monolithics

The monorepo world

Monolithic repositories for source code are a well studied topic in this era of Javascript packaging, but are especially valuable when deploying monolithic services bundles composed of many projects. Javascript and Typescript are particularly inclined to this many-into-one project architecture, as build artifacts may include ReactJS apps, CLI tools, or serverless functions.

There are a wide variety of tools out there that support intersecting monolithics with traditional package.json nowadays, including yarn, npm 7, Turborepo, and lerna. These are popular and reasonable choices for starting a new family of projects.

How do you manage versioning, though? Some tools are unopinionated, others like lerna are heavily opinionated. Also, how do you manage release notes and communicate impactful changes to your customers, both internal and external?

Example: Continuous Semver

Traditionally, we’ve answered this question using Semantic Versioning, where major, minor, and patch version numbers each have localized meaning within the version history of a particular project.

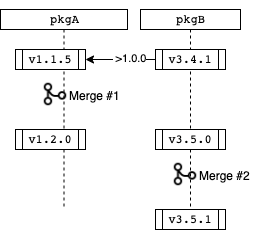

Say B depends on A:

Usually, the maintainers of pkgB would decide on some restrictive semver rule like ^1.0.0 so that patch level changes are maintained, but functional or generational changes are not automatically adopted. But this is a lot of work for a small team! Especially if both pkgA and pkgB are owned by the same engineering team, with packaging being used to allow reuse of a component between multiple build artifacts.

If a more permissive semver rule is used, like >1.0.0 or even *, then additional burdens are placed on top of the developers. Every time pkgA is changed, now, the developer needs to remember to also bump the latest version on pkgB, modify it’s release notes, and perform other tasks.

This is a lot of process, and humans will get it wrong.

How do we build a process that, by its very nature, eliminates the opportunity for developer error in this situation?

Discontinuous Semver

Here at Stateful, for our multipackage monorepos, we use something called Discontinuous Semver. Discontinuous, in that not every package has a unique version at every numerical increment. And semver in that we still hold true to the core Semantic Versioning concepts: major, minor, and patch, each communicating different levels of possible “risk” in the package.

Fundamentally, Discontinuous Semver boils down to two important realizations. First, end-users rarely understand the levels of risk involved in different versions beyond “it’s broken, so I need to upgrade”, which allows us to push process in that direction.

Second, we can have releases that have version changes that imply risk but are not actually risky. For example, if we have a package that increments the minor version number but does not actually contain any changes, we’ll still impact end-users in the same way: they will wait until something is broken on the version they’re currently using, and then jump to whatever highest version seems vaguely plausible or works with minimal effort.

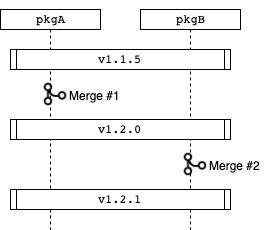

This allows us to spread versioning across multiple packages in lockstep, rather than in isolation:

Here, the versions of pkgA and pkgB are incremented in unison. This makes sense at a variety of levels, especially as pkgB does depend on pkgA, but minor (or even major) changes to pkgA do not necessarily mean that downstream users of pkgB will be similarly impacted.

That is a cognitive penalty we can safely defer to end-users because it encourages an “error towards safety” on the part of the user.

Implementation: Lerna for fast Discontinuous Semver

While there are many reasons to use some type of package hoisting tool, we eventually settled on Lerna for its support of fixed mode versioning. Fixed mode versioning moves all of the packages in the monorepo in lockstep, just like the diagram above.

Each time we publish a PR, we include a label that indicates which semver value to bump: semver:major, semver:minor, or semver:patch.

This label is then consumed by a GitHub Action to automatically bump the latest version, tag the release, and commit the change back into the repository:

First, we start by making sure the PR has the specified labels in place, and is running on the correct Ubuntu build.

on:

pull_request:

types: ['closed']

name: CICD - DEV - Bump and Publish

jobs:

bump_patch:

concurrency: 'bump'

if: contains(github.event.pull_request.labels.*.name, 'semver:patch') && github.event.pull_request.merged == true

name: bump_patch

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

Then we set up the environment, and build the tree.

steps:

- name: Use Node.js

uses: actions/setup-node@v1

with:

node-version: 14.17.2

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

fetch-depth: 0

- name: Build Tree

run: npm ci && npx lerna bootstrap && npx lerna run build

Next, we tell lerna to update the version by the patch step (duplicate and change this sequence for major and minor). We add and commit the files, and then push the change back to the repository.

- name: Bump Patch Version

run: |

git pull

git switch main

npx lerna version patch --yes --no-git-tag-version

git config --global user.email "goat@stateful.com"

git config --global user.name "The GOAT"

git add -A

git commit -m "Bump: $(cat lerna.json | jq -r .version)"

git push

Finally, we make sure we increment the tag in the repository so that each release is tagged correctly:

- name: Bump git tag

run: |

VERSION=`jq -rc ".version" lerna.json`

git tag v${VERSION} || true

git push --tags || true

With these GitHub Actions in place, merging a PR causes the latest version numbers to bump, a new tagged release to be issued, and the package.json files to be updated correctly. Lerna handles all of those details automatically, which substantially reduces the number of manual changes we had to do when dealing with our primary integration repository.

When you have many interdependent packages, managing the versions when a core package changes is a phenomenal amount of work. Using Lerna and a discontinuous semver can substantially increase development velocity by allowing individual developers not to have to worry about bumping version numbers on dependent packages.

Downsides

This approach is definitely counter to some of the other trends in JavaScript, and disagrees with some aspects of the tooling (and especially, has a slight negative impact on version control).

Churn in your package.json files

Because the versioning is moving in lockstep, lerna will increment the version field in each package.json every time the global version is incremented. This also induces churn in the package-lock.json files.

The primary impact here is that code diffs get a little noisier (unless you exclude package.json files entirely), and “lines of code changed” metrics have a constant N attached to each commit.

That’s acceptable, though, because you shouldn’t be using LOC metrics anyways.

What about pkgC?

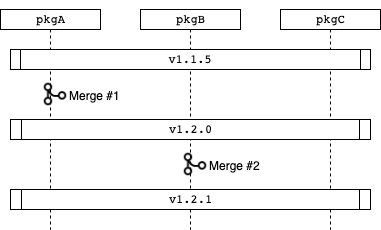

What about pkgC, an unrelated package in the same monorepo? It’s version is bumping, but it doesn’t have any changes:

There are a couple of different side effects of this approach here. The first is that the version of pkgC is changing as merge #1 and #2 come in, but there is no changes at all to pkgC. Second, any changes to pkgC will again induce changes against the versions of pkgA and pkgB.

It’s not ideal, but still encourages erroring on the side of safety for the end-user. We could split the monorepo into subsections, each with its own “root” version (think parallel lerna stacks), but that confuses the monorepo management tooling and dependency resolution in a way that will require further coding.

Maybe you have a better suggestion? :)

Churn in package.json and package-lock.json

Adding new projects to our repository using lerna places a new package-lock.json file in each project directory. While this allows us to separate dependencies out (some packages require specific versions of TypeScript, for example), it also means that every new project we add is also paired with a ~20kloc diff. This basically renders LOC statistics useless which is largely supported by research.

Customer clarity

By far, the biggest drawback to Discontinuous Semver is the impact to enduser clarity. In theory, with traditional semver the user is able to easily determine the riskiness of a particular change. With Discontinuous Semver, the user is only able to establish a minimum level of risk - which is, in all honesty, a much more reasonable stance to take.

There are only three situations that users, in the real world, upgrade packages: when Dependabot tells them to, when something is broken and they need a fix, or when there’s a new feature that has just come out. All three broadly require the same level of caution and validation by the user, whether the version is a major, minor, or a patch, for the very simple reason that no one can (or should!) trust anyone else to accurately assess the impact of a particular change.

Yes, release notes can and should be used to assist in this communication exercise, and advise on specific changes necessary to support a new release, but those are rarely as verbose, useful, or targeted as the user would like.