Webhook Rate Limits and Throttling

A webhook is a technique for an app to transfer real-time information and data to other applications. Webhooks are driven by events rather than requests. In other words, webhooks are events sent from the app to the consumer.

Rate limits and throttling in webhooks are a must-have practice. Since webhooks primary purposes is to send data, there should be limits to the amount of data being sent, for many reasons you will learn about below.

What is the difference between rate limits and throttling?

Rate limits: is a policy that limits the number of events the webhook accepts in a window of time. You can create multiple limits with specific window sizes, from milliseconds to months. All the webhook events that exceed the limit will be rejected. In other words, it controls the consumption of resources used by the webhook.

Throttling: is a policy that queues events that exceed limits for possible future processing in a window of time. Throttling is a technique to handle users that are exceeding their provision capacity. The webhook eventually rejects the event if the processing cannot occur after several retries. You can configure how many times the webhook will retry and their delay.

The Rate Limiting and Throttling techniques limit all webhook events but have different purposes: rate limiting protects a webhook by applying a hard limit on its access. Throttling shapes webhook access by smoothing spikes in traffic.

Why is rate limiting and throttling important?

There are three main reasons why applications rate-limit:

- Avoid resource starvation and maintain service availability and stability. Rate limiting and throttling help with the common problem of running out of resources that can cause slow performance. There is a certain level of performance you should ensure for your clients. For example, you want to avoid the cost of dispatching too many webhooks within too short of a time period (provisioning additional computers or networking expenses), or you want to avoid accidentally saturating known bottlenecks such as network bandwidth. It's a good practice to ensure stability and consistency across all your different users.

- Cost control is also a common reason to use rate-limiting. Giving a certain number of requests in a given time interval is good because more requests can cost more money. Rate limiting is a useful technique to limit those requests within a time frame and save moeny.

- Scalability if your application blows up in popularity, there can be unexpected spikes in traffic, causing a severe lag time. Rate limiting and throttling in webhooks help with a smooth transition of data.

- Security Rate limits protect against number of events in webhooks, if the webhook becomes overload it can cause performance and security issues.

Rate Limiting Techniques

There are three main rate-limiting techniques: Fixed Window, Token Bucket, and Sliding Log.

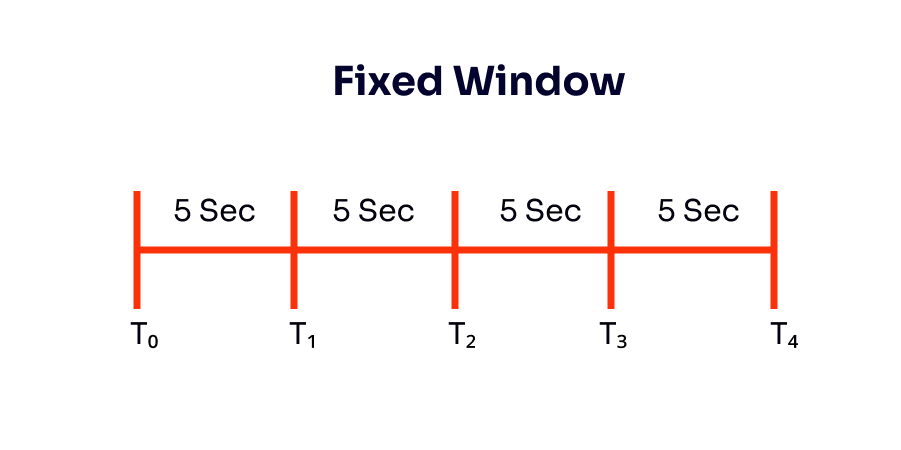

Fixed Window

Fixed Window is an algorithm that uses a window size of time in seconds for processing webhook events. The events will be discarded if they exceed a threshold, for example, a fixed block of time of 5 seconds where ten webhook events per window are allowed - as you can see in the image below. Within that 5 second window, any requests in excess of 10 will be dropped. At T₁, the number of allowed requests is reset to 10. There could be multiple time windows stacked across time.

This produces very spiky traffic under load - at each 5-second interval, ten requests will be sent, and then the rest of the time, the network will be idle.

An advantage of this approach is that it ensures that more recent requests will be processed first without being starved by old requests.

But there are problems with this technique. If you consume the request limit at the beginning of the time window (10 webhook events in 1 second), you won't be able to make requests in the rest of the time window (4 seconds), which is a waste of resources. Also, if many users wait for a reset window, they may stampede the webhook simultaneously.

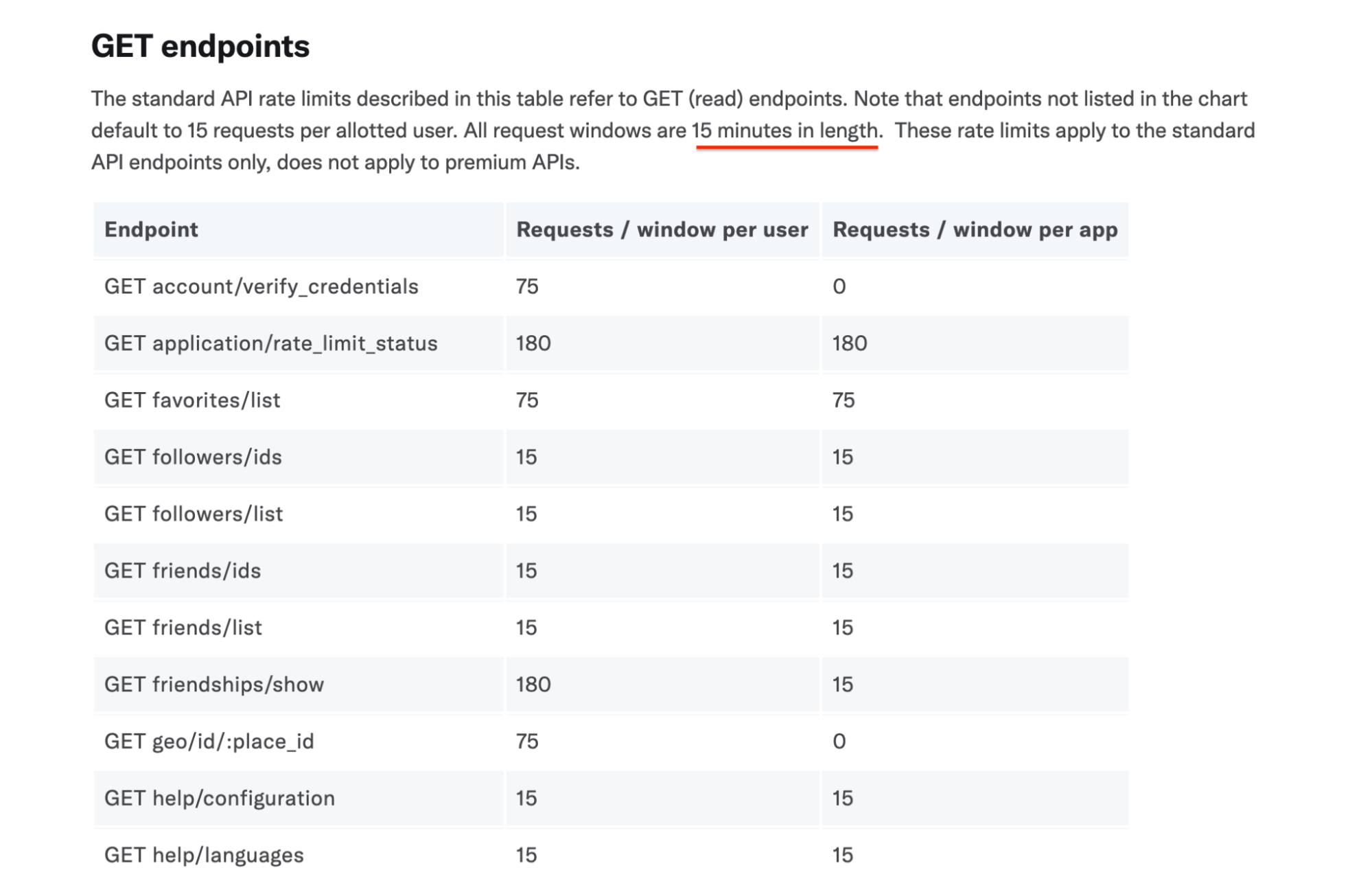

The following image is an example of the fixed window technique on the Twitter API. The endpoint has "15 minutes in length" per window. So, you can get 75 account/verify_credentials per user in 15 minutes.

You have limits associated with your API developer key. The following is the error you will receive if you exceed a rate limit in Twitter, which is called the throttling exception. The server rejects your requests because it has been exceeded the limit of requests per time unit (75 requests in 15 min)

{ "errors": [ { "code": 88, "message": "Rate limit exceeded" } ] }

Token Bucket

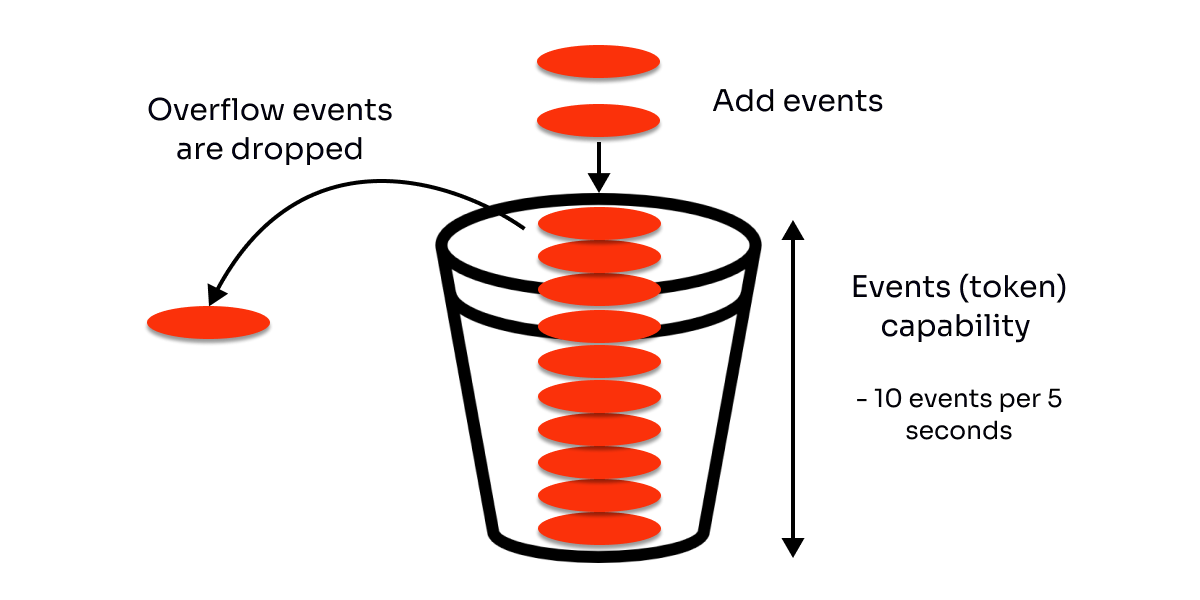

Let's think of a bucket that's been filled with water. There are two main concepts in the bucket algorithm. One is burst, and the other is sustain. Burst is the maximum number of events that can be handled (let’s say 10 events). If you have a really large bucket, you can handle many bursting webhook events that are coming in at a particular moment in time. Sustain is the rate at which we refill events (tokens) based on a time interval (per second or minute - let’s say 5 seconds).

We can assign a bucket with a specific amount of tokens to each client to limit the events per client on a time period. When a user exhausts all their tokens in the 5-seconds time interval, the events are discarded until their bucket is refilled.

Pouring more events will mean pouring more water into the bucket.

Let's imagine the webhook will fill every request as a bucket fills with water. When reaching the limit capacity of 10, it will start getting throttled.

The bucket algorithm allows you to encode the concept of burstiness and ensure that if different applications make requests simultaneously, your webhook will be able to handle it and have a healthy sustain rate.

The bucket algorithm is very common in AWS, Azure, or any cloud service.

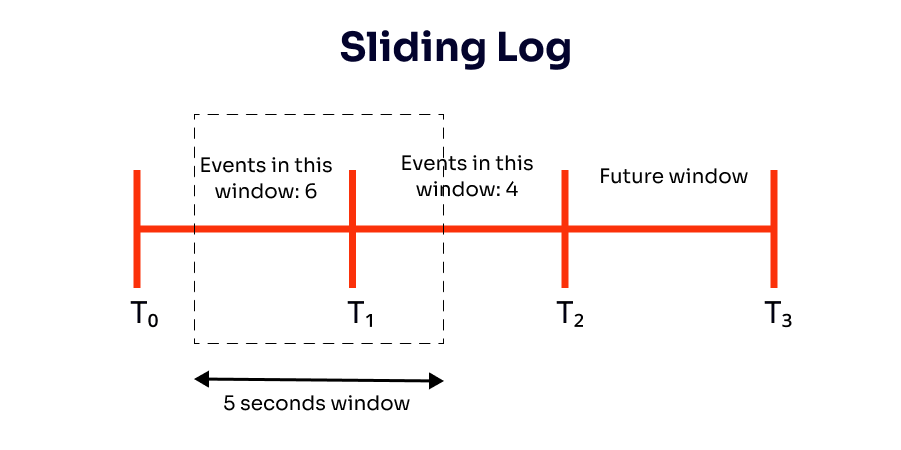

Sliding Log

The sliding log algorithm calculates the request rate in real-time (instead of calculating it in each request window like the Fixed Window approach). Rate-limiting with Sliding Logs entails keeping track of a timestamped log for each consumer request in a single sorted set. These logs are normally saved in a hash set or table that is time-sorted. Logs with timestamps greater than a particular threshold are deleted. They are also discarded if the request count exceeds the threshold.

The request rate is the sum of the log entries for that unique user. For every new request, it's necessary to access the logs and filter out entries older than 5 seconds - for a 5 second based rate limiter.

However, storing a great number of logs for each event can be expensive and calculating the number of events across multiple servers.

Error retries - exponential backoff retry strategy

Rate limits and throttling helps to limit the number of events and queue them when it exceeds their limits. But, what happens when the webhook fails? What's the best way of handling failed webhooks?

There are two approaches: the quick approach and the best approach.

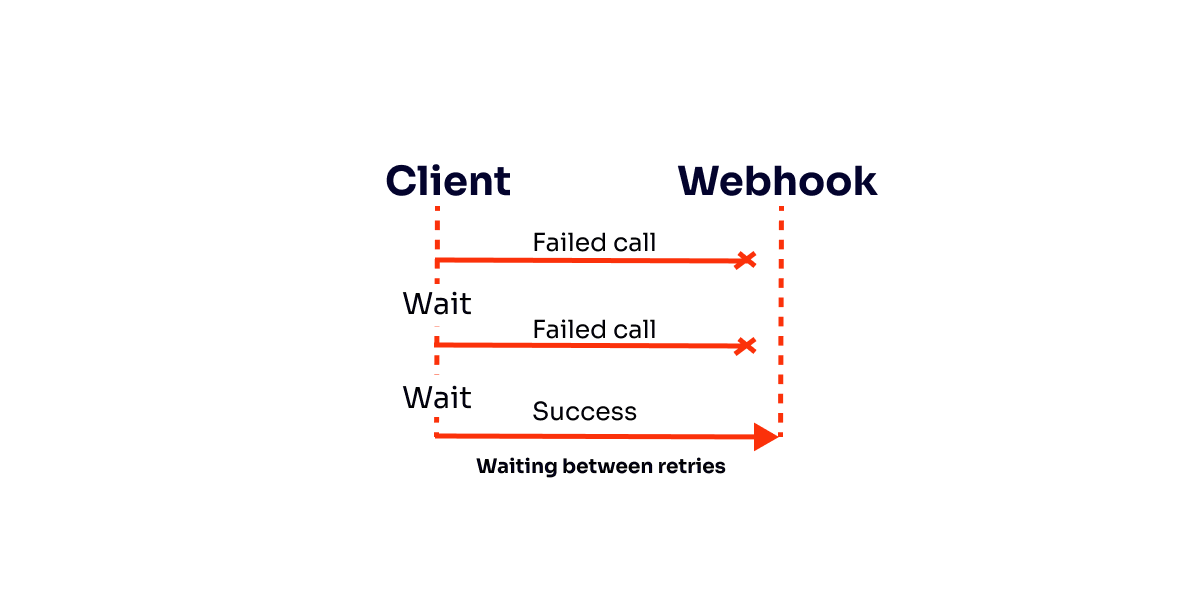

The Quick Approach: retrying in a period of time without intervals between the retries, for example, retrying three times in a row when a webhook fails. This could be ineffective because a failed event can go to a retry queue and that was processed again and fail again and again until all attempts are exhausted, and it throws a DLQ (dead-letter queue), which means that all retries would fail without the opportunity to recover in time to receive the event.

The problem with this approach is that the time window for the retries is really short since all retries are performed in a row. Short time windows for webhooks retries could be ineffective since it can demand more time to recover than time to reprocess the events.

The Best Approach: we can implement the exponential backoff retry strategy! A backoff algorithm ensures that when the webhook can't send events, it is not overwhelmed with subsequent events and retries. It will "backoff" from the webhook, distributing the failed message through different queues and introducing a waiting period between the retries to give the webhook a chance to recover. When a webhook event fails, you should retry the event in a period of time to eventually succeed while trying to minimize the calls made. If all the attempts to trigger the webhook fail, the failed message will go to the end of the queue.

If the webhook is unavailable or overloaded, sending more requests will only worsen the problem, resulting in a waste of infrastructure resources. Temporarily backing off from adding more requests can smooth the traffic 🚙.

With the backoff algorithm, it's possible to determine how much time to wait between the retries.

So, the main problem to solve is the wait time. Sending events too soon puts more load on the server, while waiting too long introduces too much lag.

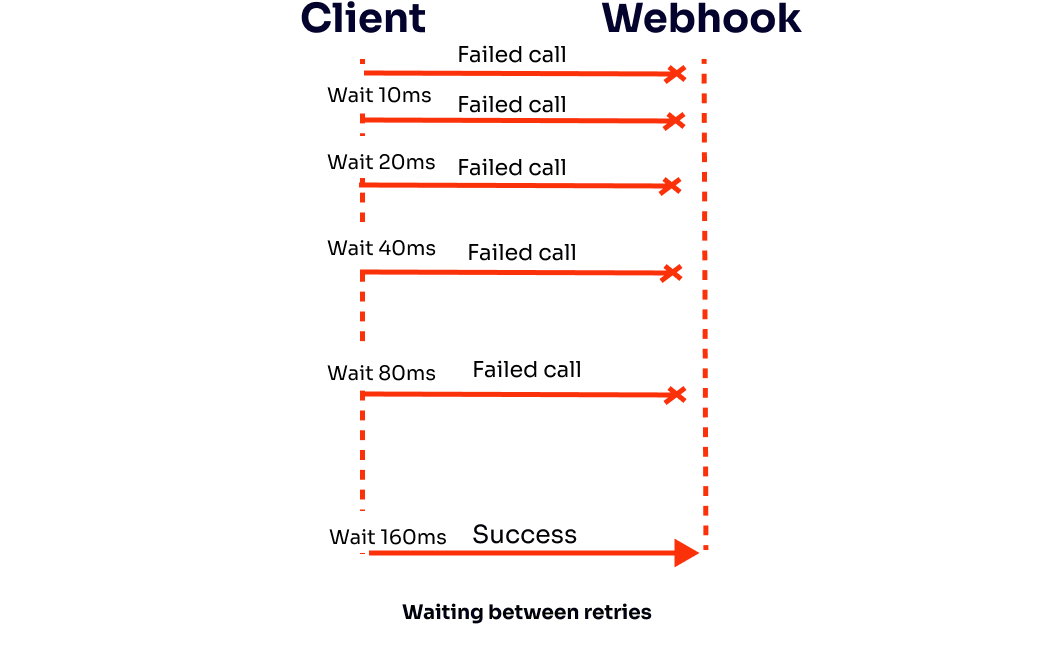

The exponential part of the algorithm is when the waiting time grows exponentially to maximize the chances of success by not creating requests too soon or too late — making the first tries happen quickly, reaching more extended periods with more retries.

For example, if the first retry is 5ms, and the following retries are double the previous values, the waiting time is 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320…

Rate Limiting Recommendations and Conclusions

There are two perspectives for rate-limiting recommendations: server perspective and client perspective.

Server perspective

- Decide on an "identity" for throttling a webhook: it's necessary to uniquely identify the webhook event through an ID.

- Determine your webhook traffic volume breaking point: we don't want to give our clients too little or too much capacity or flexibility, so the webhook is available and can't exceed what is capable of handling. You can determine the capacity of the webhook and traffic volume through load test. If the webhook's load test points can handle 100 events, you don't want to give throttling limits of 150 because it could get overwhelmed.

- Using rate-limiting libraries: or build your own if the libraries are not suitable for your use case. For example, Express Rate Limit or Google Guava library for Java.

Client perspective

- Use a retry policy for clients: to tolerate failure. A good retry policy, as mentioned before, is exponential backoff.

- Use the jitter concept: this means adding a little bit of randomness between the retry waiting period. If it was established that the waiting period between retries is 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 milliseconds, do instead 5.23, 10.62, 20.23, 40.41, 80.79, for example. The reason is that if many webhooks events are happening all at once and they're getting throttled, you don't want them all to retry at the exact same time. If you hardcode

5, the events will retry at that moment and will probably be throttled again. Using jitter or randomness, you can ensure that you're not layering your request all at once but distributing them over time with a sense of randomness. - Retry limit: don't retry over and over until infinity. Give the webhook a maximum retry number, for example, 5.

- Be fault-tolerant: means a system's ability to continue operating uninterrupted despite the failure of one or more of its components. If the webhook fails, it should have mechanisms for retrying (exponential backoff), and the application should keep working.

Before your go..

References

- Rate-limiting strategies and techniques

- What is Rate Limiting / API Throttling?

- Webhooks: The Devil in the Details

- How to implement an exponential backoff retry strategy in Javascript

- Handling failed webhooks with Exponential Backoff

- Understanding Rate Limiting Algorithms

- Rate Limiting

- Fault Tolerance