How to Secure Your HTTP APIs

If you are building an application with HTTP APIs that serve sensitive data, one of the key considerations is security. You want to ensure that callers of your API are authorized to make those calls before they are granted access to sensitive information or perform sensitive operations.

This post will review a few HTTP API access control approaches, from simple API keys to OAuth. It will also discuss a more complex yet flexible scheme that enables your customers to influence how access control decisions are made, based on how we approached securing API traffic to Stateful.

A Multi-Tenant Cloud Application

Most web applications with APIs built today are multi-tenant. They have many customers or users (called tenants). The expectation is that your secure REST APIs enable your tenant’s access and control over their data, but not the data of other tenants of your app.

Let’s say you are building an application that enables stores to track their inventory. Each store is a separate tenant of your app. You expose REST API for inspecting and modifying a store’s inventory. It could look something like this:

app.get(‘/api/store/:storeId/inventory’, searchStoreInventory);

app.post(‘/api/store/:storeId/inventory’, createStoreInventoryItem);

app.get(‘/api/store/:storeId/inventory/:itemId’, getStoreInventoryItem);

app.put(‘/api/store/:storeId/inventory/:itemId’, updateStoreInventoryItem);

app.delete(‘/api/store/:storeId/inventory/:itemId’, deleteStoreInventoryItem);

You have signed up multiple stores as customers of your app. Your application security requires that each store can access and manipulate its own inventory, but not the inventory of other stores. Moreover, you may want to distinguish between individual callers acting on behalf of a single store, with some having only the read access to the inventory, while others both read and write.

Authentication and Authorization

It is useful to secure your HTTP APIs in two separate steps: authentication and authorization.

Authentication is the process of proving the identity of the caller. When the authentication process is complete, you know whether Daisy or John made the call.

Once you understand who is making the request (who the authenticated user is), the next step is to determine what permissions the caller has. This process is authorization. When the authorization is complete, you know that John can only look up the inventory of the “Pet’s Parlor” store, while Daisy can both look up and modify the inventory of the “International Burger Machines” store.

It is interesting to note that as a developer securing the HTTP APIs at the application level, you mostly care about the permissions of the caller, not their identity (unless required by law, web server logs, or for auditing purposes). When someone shows up in a grocery store to buy a bag of potatoes with cash, the clerk only cares if they carry the prerequisite amount of money, not who they are. This is important because it allows for flexibility as to when and where the authentication and authorization decisions are made.

API Keys

Using API keys has been the norm in securing HTTP APIs of RESTful web services for a long time, and many established applications and platforms like Stripe or AWS continue using API keys today.

An API Key is a secret shared between the application and the caller. The caller authenticates a call to the HTTP APIs by proving ownership of the API key. It can be as simple as attaching the API key to the request, for example, in the Authorization HTTP request header or a URL query parameter. It can also be as complex as digitally signing selected parts of the request payload with that key.

HTTP GET /api/store/123/inventory

Authorization: Bearer {api-key}

The example above is using the Bearer scheme of the Authorization HTTP header, which is the preferred way of passing in API keys in web API calls when the user agent is an application. Some secure API endpoints use the HTTP basic authentication scheme instead. In this scheme, the token passed in is an encoded combination of a username and password, and as such more suitable in situations where the user agent is a web browser with a human in front of it.

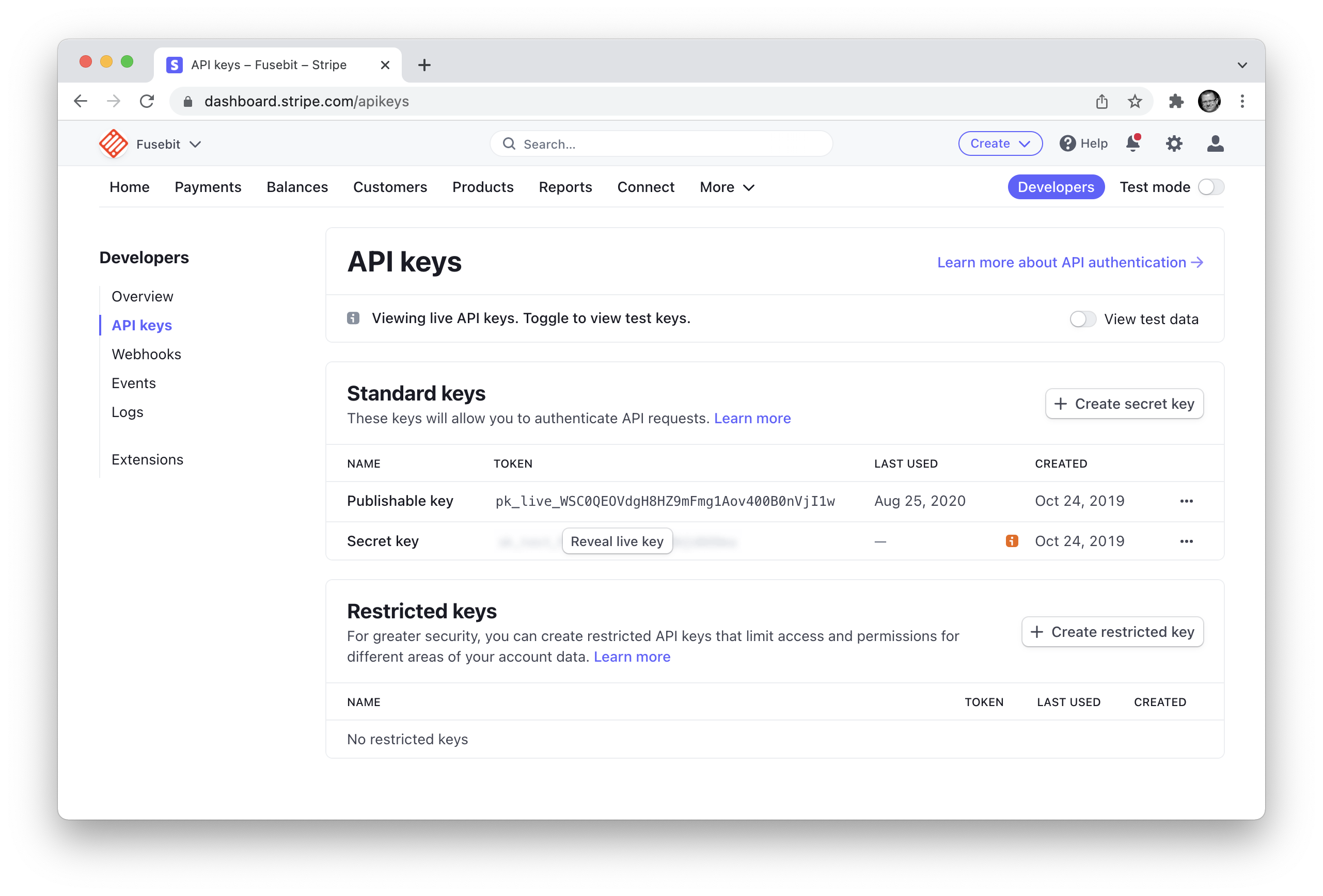

Since API keys are usually scoped to a particular tenant of an application, proving ownership of an API key implicitly authorizes the caller to perform operations on that tenant. If the authorization decisions require finer granularity, like in our store inventory app example, you can choose to have a concept of API keys with specific permissions associated with them. This is the mechanism Stripe implemented, called “Restricted keys” in the screenshot above.

From the perspective of the developers starting to work with your APIs, the biggest advantage of API keys is simplicity. It is a simple concept to start with, and it is easy to attach an API key to a request using any HTTP client.

API keys have several drawbacks though, the severity of which depends on your specific application.

Delegating access to your APIs is only possible through sharing the API key. This is akin to sharing your Twitter password with your marketing team, your cell phone PIN with your kids, or your bank account password with a financial aggregation application. Over time it leads to dilution of control and overall reduction of security. It also makes key rollover (next) harder to manage.

API keys are long-lived, and compromised keys require a rollover. During the rollover, a new key must be generated, and every system using the old key must be updated. This means work for developers working with your APIs and for you. This is usually done in three stages to reduce downtime. First, a new key is generated, and your app accepts both old and new keys. Then, all systems calling your APIs are reconfigured to use the new key. Lastly, the old key is removed from your app, and it only accepts the new key going forward. This process can take a long time as it is usually human-driven.

OAuth

The OAuth mechanism was introduced to address some of the issues with API Keys and has since become the de-facto standard for securing modern HTTP APIs.

OAuth replaces the long-lived API keys with short-lived session tokens called access tokens that the caller must obtain before making a call to your HTTP API. OAuth also defines several protocols called flows that allow various types of applications to obtain the access token to call your APIs. These can be traditional web applications, mobile applications, single-page apps, or server applications.

Once obtained, the caller attaches an access token to the request, typically as a Bearer token in the Authorization header:

HTTP GET /api/store/123/inventory

Authorization: Bearer {access-token}

OAuth conceptually decouples the process of obtaining an access token from the application that accepts it. You can implement the OAuth authorization logic as an integral part of your application. However, unlike API keys that your application was managing for its tenants or user accounts, using OAuth enables you as an application developer to instead trust an external authorization server to issue the access tokens for your APIs. This removes a lot of the complexity from your app and allows for centralization of authorization decisions, which is an important governance and specialization advantage in larger organizations.

How are authentication and authorization decisions made when your APIs are secured with OAuth? The OAuth spec allows for some flexibility there. On one end of the spectrum, an access token may represent an authenticated caller, leaving all the authorization decisions to the application. On the other end of the spectrum, the authorization server may associate authorization policies (or permissions) with the access tokens it issues, leaving the app with a simple access control decision that depends on the context of the API call using that token (e.g. the endpoint being called).

As a developer, you have a choice of many third-party authorization services to trust for the issuance of your access tokens. For example, Okta and Auth0 provide authorization services that aspire to solve not only the authentication but also the authorization problem. Google, Microsoft, Facebook, GitHub, and many other popular platforms allow you to rely on their authentication services so that users of apps using your APIs can “Log in with Google” to obtain their access tokens. In the latter case, once you know the identity of the caller, all authorization decisions are going to be part of your application logic.

The benefits of relying on external identity providers in your application are many. For one, this is their area of expertise that you can leverage without reinventing the wheel. Another one is that by delegating caller authentication, you are removing an important attack vector and a potential surface area for distributed denial of service attacks by malicious actors from your application. Validating an access token issued by a single trusted identity provider is a simpler problem to solve than preventing attacks by unauthenticated callers.

The OAuth 2.0 specification allows for this flexibility of interpretation by leaving many of its aspects “extensible”. One interesting aspect left undefined is the structure of the access token itself. In general, your application should treat the access token as an opaque string, and pass it over to the authorization server for validation. However, a complementary JSON Web Token for OAuth 2.0 Profile specification prescribes the access token to be a JSON Web Token (JWT) - a signed, base64 encoded JSON structure. This allows your application to validate the token and extract trusted, useful information from it that the authorization server included, all without the overhead of communicating with the authorization server at runtime. A sample JWT access token payload may look like this:

{

"https://stateful.com/profile": {

"accountId": "acc-5beef9fb55a74208",

"subscriptionId": "sub-3608cef5e91d4def",

"userId": "usr-4a87f371e00e41aa"

},

"iss": "https://stateful.auth0.com/",

"sub": "google-oauth2|109599723937143983800",

"aud": "https://api.us-west-1.on.stateful.com",

"iat": 1640267302,

"exp": 1640353702,

"azp": "NIfqE4hpPOXuIhllkxndlafSKcKesEfc",

"scope": "offline_access"

}

The properties in the payload of the JWT token are called claims. Two of the required claims, iss and sub, represent the bearer's identity. The iss claim describes the issuer of the token (the authorization server), and the sub claim is the unique identity of the caller in the issuer’s universe. The presence of these two claims in the JWT access token allows you to rely on the authorization server to perform caller authentication, and you can implement your own authorization story from there.

Beyond Simple OAuth - Bring Your Own Issuer

In most situations, a multi-tenant application using OAuth is pre-configured to trust a fixed set of authorization servers. For example, you can accept access tokens issued by Google or GitHub, and provide this fixed choice to callers of your HTTP APIs.

However, there are situations when you want to allow customers of your application to tell you which authorization servers they want your application to trust. This is often the case when your application provides a service to fellow developers building their own apps which already have an opinion about how to authorize their users. Stateful is just such an application - it is an integration platform for developers who want to embed integration capabilities into their apps. We wanted customers of Stateful to be able to tell us how they want to create their access tokens to call Stateful management APIs.

We enable customers of Stateful to configure their own OAuth issuers that Stateful will trust. This choice is made on a per-tenant basis. In the context of the sample store inventory app introduced at the beginning, it means that each store owner can configure a set of trusted token issuers (corresponding to the iss claim in the access token) that the store application will accept tokens from. The app can validate access tokens from that issuer using either an explicitly specified public key, or by discovering such key at runtime using the JWKS endpoint of the issuer.

How does it all come together? When we onboard a new customer to Stateful, we assign them a unique storeId representing the tenant in our system, and allow them to specify one or more trusted token issuers (corresponding to the iss claim in the access token), along with the public key or JWKS endpoint. We store the issuer information associated with the storeId for later.

Now, at runtime, a caller makes an HTTP request to one of the store inventory APIs and presents an access token, presumably obtained from the trusted issuer of that store:

HTTP GET /api/store/123/inventory

Authorization: Bearer {access-token}

The store inventory application will validate the token by:

- Determining the set of trusted issuers based on the storeId in the request URL (“123” in the example above).

- Using the iss claim from the yet unverified access token to determine the specific issuer the access token was allegedly created by, and making sure it is one of the issuers configured for the storeId.

- Obtaining the public key of the issuer, either stored directly at bootstrap, or using the JWKS endpoint.

- Validating the signature of the JWT token, as well as performing other validation steps as per JWT specification.

- If successful, the application now has determined the identity of the caller, which is uniquely defined by the (iss, sub) pair of claims from the access token.

- Knowing the identity, the store application can proceed to make an authorization decision using application-level mechanisms to determine if the caller is granted access or restricted access.

Conclusion

There is no single “right” way of securing HTTP APIs of web services, but the overwhelming trend in this space and the API security best practices is to use OAuth. The OAuth mechanism offers a lot of flexibility in deciding how authentication and authorization decisions are made, and supports more advanced scenarios that enable you to embrace your customer’s authorization servers.